Calorie Clarity: Master Your Energy Balance

The Evidence-Based Guide to Daily Caloric Intake Needs Across Age Groups and Activity Levels

Ah, calories—those tiny units of energy that seem to dominate nutrition conversations everywhere from scientific journals to social media feeds. Whether you're scrolling through fitness influencer content or reading the latest nutrition research, calorie counting remains one of the most discussed—and perhaps misunderstood—aspects of nutrition science.

But what exactly is a calorie? Is tracking them really the golden ticket to weight management that many claim? And why do some nutrition experts praise calorie counting while others condemn it as outdated or even harmful?

As we dive into this caloric conundrum together, we'll explore not just what calories are, but how they function in different bodies, how many you might need based on your age, sex, and activity level, and whether all calories truly affect your body in the same way (spoiler alert: they don't). We'll examine both the scientific evidence supporting calorie awareness and the emerging research suggesting its limitations.

What Is a Calorie?

Let's start with the basics. Scientifically speaking, a calorie is a unit of energy. Specifically, one calorie is the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of one gram of water by one degree Celsius (Harvard Health Publishing, 2020). However, when we talk about calories in food, we're actually referring to kilocalories (kcal), which equal 1,000 of these small calories. For simplicity's sake, nutritionists typically just call these kilocalories "calories."

A calorie, in food terms, is simply a measure of the energy that food provides to your body. When you consume food, your body breaks it down through various metabolic processes, releasing this stored energy to fuel everything from basic bodily functions like breathing and cell repair to more demanding activities like running or even thinking (yes, your brain is quite the energy consumer!).

Different macronutrients provide different amounts of energy:

Carbohydrates: ~4 calories per gram

Proteins: ~4 calories per gram

Fats: ~9 calories per gram

Alcohol: ~7 calories per gram

This explains why fatty foods tend to be highest in calories—they pack more than twice the energy per gram compared to proteins and carbohydrates. Foods like fried items, fast foods, nut butters, cheese, and fatty meats naturally contain more calories by weight than their leaner counterparts.

But—and this is crucial—these numbers only tell part of the story. As we'll discuss later, the quality of those calories and how your body processes them matters tremendously.

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): Your Body's Energy Baseline

Before we dive into how many calories different people need, we need to understand the concept of Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR).

Your BMR represents the minimum amount of energy your body needs to perform its essential functions while at complete rest—think maintaining organ function, breathing, circulating blood, and adjusting hormone levels. It's essentially what your body would burn if you stayed in bed all day without moving.

Several factors affect your BMR:

Age (BMR typically decreases with age)

Body composition (muscle burns more calories than fat)

Sex (biological differences affect metabolism)

Genetics

Hormonal factors

Calculating Your BMR

While laboratory tests like indirect calorimetry provide the most accurate BMR measurements, mathematical equations offer reasonable estimates. The two most commonly used formulas are:

Harris-Benedict Equation:

Men: BMR = 88.362 + (13.397 × weight in kg) + (4.799 × height in cm) - (5.677 × age in years)

Women: BMR = 447.593 + (9.247 × weight in kg) + (3.098 × height in cm) - (4.330 × age in years)

Mifflin-St Jeor Equation:

Men: BMR = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) + 5

Women: BMR = (10 × weight in kg) + (6.25 × height in cm) - (5 × age in years) - 161

Research suggests the Mifflin-St Jeor Equation tends to be more accurate for most people (Frankenfield et al., 2005). However, it's important to remember that these are still estimates. Your actual BMR might vary by up to 10-15% from these calculations due to factors like muscle mass, body composition, and individual metabolic variations.

Speaking of muscle mass—it's worth emphasizing that muscle tissue is metabolically more active than fat tissue. This means that two people of the same weight, height, age, and sex might have significantly different BMRs if one has more muscle mass. For every pound of muscle you have, your body burns approximately 6-10 additional calories per day at rest, compared to just 2-3 calories for a pound of fat (Westcott, 2012).

Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE): The Complete Picture

Once you know your BMR, you need to account for your activity level to determine your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)—the total number of calories you burn each day. This includes:

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): 60-70% of TDEE

Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): 10% of TDEE (energy required for digestion)

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): Varies widely (energy for daily movements like fidgeting, standing, walking around)

Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT): Varies widely (planned physical activity)

To estimate TDEE, multiply your BMR by an activity factor:

Sedentary (little/no exercise): BMR × 1.2

Lightly active (light exercise 1-3 days/week): BMR × 1.375

Moderately active (moderate exercise 3-5 days/week): BMR × 1.55

Very active (hard exercise 6-7 days/week): BMR × 1.725

Extremely active (very hard daily exercise or physical job): BMR × 1.9

For a simpler approach, you can estimate your weight maintenance calories by multiplying your weight in pounds by:

13-14 for sedentary individuals

15-16 for moderately active individuals

17-19 for very active individuals

For example: If you are 120 pounds and moderately active (getting at least 30 minutes of physical activity a day, such as active gardening, walking at a brisk pace, climbing stairs), it would be 120 x 15 = 1800 maintenance calories. So to lose weight, you will need to be below this number. But remember—these are still estimates! Your actual needs may vary based on individual factors.

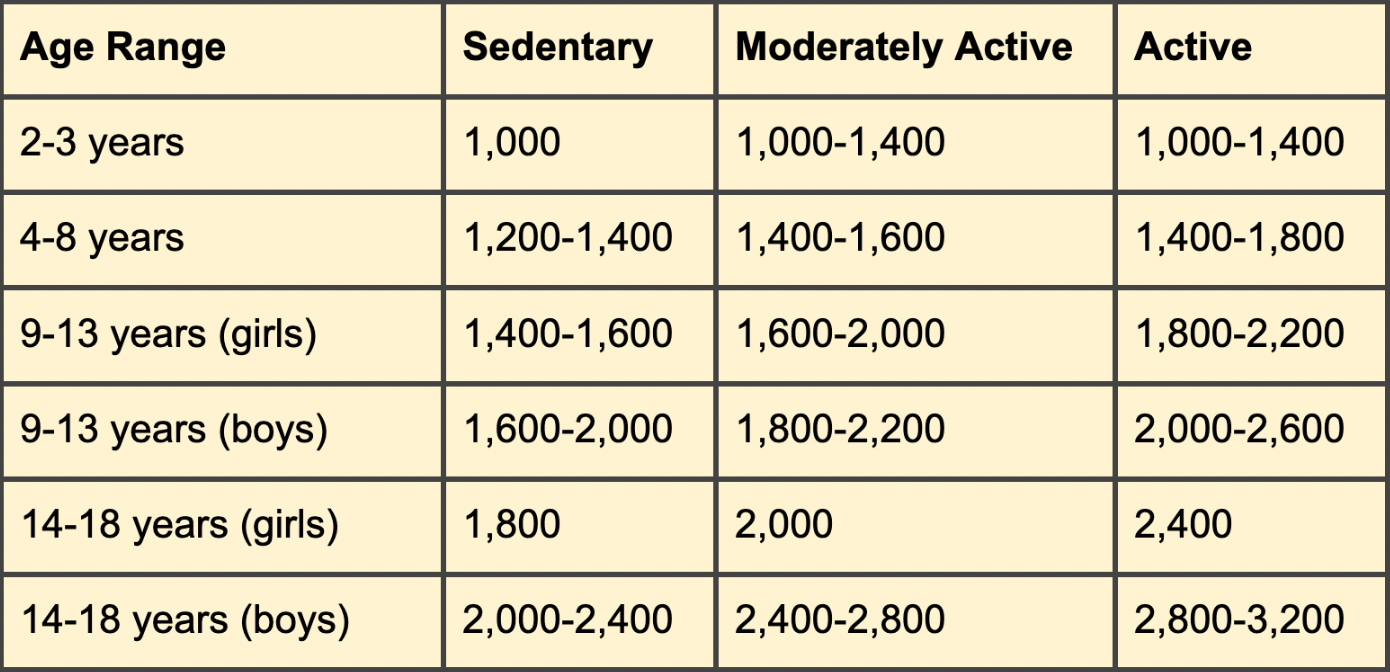

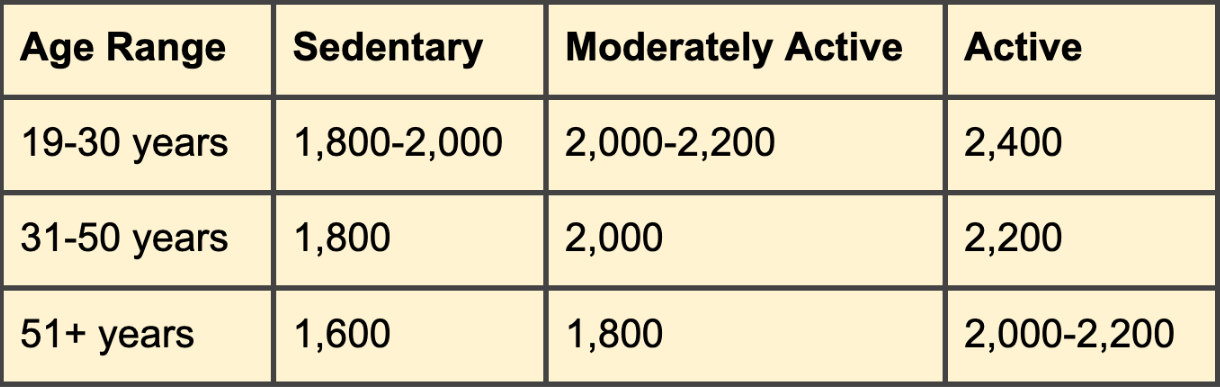

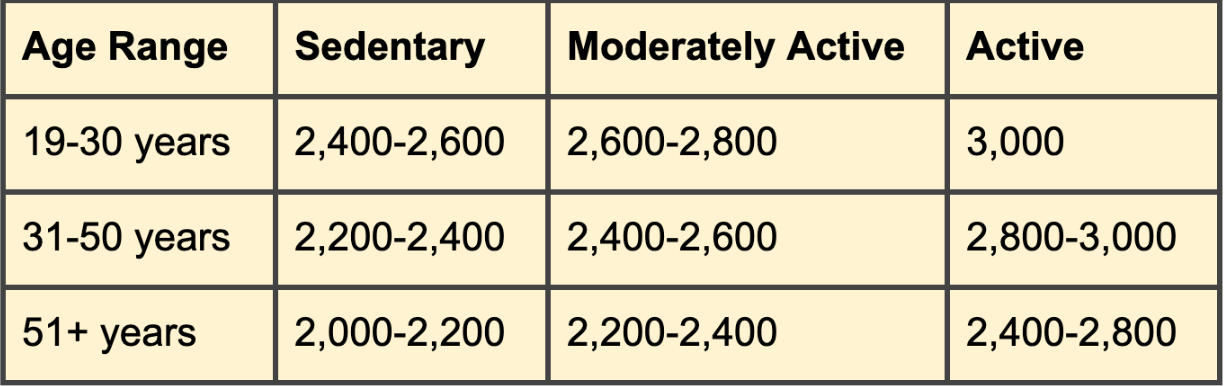

Estimated Calorie Needs By Age, Sex, and Activity Level

The following chart, based on data from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (2020-2025), provides estimated daily calorie needs. This should be used as a reference point only, as individual metabolic rates can vary significantly even among people of the same age, sex, and size.

Children and Adolescents

Adult Females

Adult Males

Important note: These figures are estimates only. A child's caloric needs can vary widely based on growth spurts, activity level, and individual metabolism. Reducing a child's calorie intake without medical supervision can risk nutritional deficiencies, impaired growth, and potentially contribute to an unhealthy relationship with food.

Not All Calories Are Created Equal: The Quality Equation

The traditional energy balance model suggests weight management is simply "calories in versus calories out." According to this view, 100 calories from candy would affect your body the same way as 100 calories from broccoli—as long as your total intake remains the same.

However, emerging research increasingly challenges this oversimplified view. Here's why the quality of your calories matters:

Key Factors That Make Calories Behave Differently

• The Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) Different nutrients require different amounts of energy to digest:

Protein: 20-35% of calories consumed are burned during digestion

Carbohydrates: 5-15% of calories consumed

Fats: 0-5% of calories consumed

This means if you consume 100 calories of protein, your body might use 20-35 calories just digesting it, leaving only 65-80 "net" calories. But 100 calories of fat might yield 95-100 "net" calories. A 2004 study found high-protein diets increased thermogenesis compared to high-fat diets with identical calorie counts (Halton & Hu, 2004).

• Satiety and Hunger Regulation Foods affect hunger hormones differently. A 2013 study in JAMA found high-glycemic foods triggered greater hunger and food cravings compared to lower-glycemic alternatives, even with identical calorie counts (Ludwig et al., 2013). To read more on high and low glycemic foods, see my recent post here!

• Nutrient Density Compare 100 calories of candy to 100 calories of broccoli:

Candy: Energy (primarily sugar) with minimal vitamins or minerals

Broccoli: Energy plus fiber, vitamins C and K, folate, potassium, and beneficial plant compounds

Both provide the same energy, but broccoli delivers a substantially higher nutrient payload supporting numerous bodily functions.

• Complex Metabolic Effects A fascinating study in Cell Metabolism showed ultra-processed foods affect metabolism differently than whole foods, even when macronutrient content and calories are matched (Hall et al., 2019). Participants on the ultra-processed diet consumed about 500 more calories per day and gained weight, while those on the whole food diet naturally ate less and lost weight.

A Real-World Example

Consider 200 calories from almonds versus 200 calories from a sugary soda:

Metabolic response: Soda causes a rapid blood sugar spike and insulin surge, potentially promoting fat storage. Almonds produce a gentler metabolic response.

Nutrient value: Almonds provide protein, healthy fats, fiber, vitamin E, magnesium, and various micronutrients. Soda provides sugar and essentially no other nutrients.

Satiety: Almonds likely keep you feeling full longer, while soda may leave you hungry again shortly afterward.

Long-term health effects: Regular consumption of nutrient-dense foods like almonds is associated with numerous health benefits, while regular soda consumption is linked to increased risk of metabolic disorders.

This doesn't mean calories don't matter—they absolutely do. But it suggests that the quality of those calories significantly impacts how your body processes and responds to them.

Calorie Counting vs. Calorie Awareness: Finding Your Balance

Let's explore two approaches to managing your caloric intake:

Calorie Counting: The Pros and Cons

Calorie counting involves tracking everything you eat and drink. While once the gold standard for weight management, its effectiveness is increasingly questioned.

Benefits:

Creates awareness of energy intake

Provides structure and guidelines

Effective for short-term weight loss

Educational about food composition

Research supports this: a 2008 study found participants who kept food diaries lost nearly twice as much weight as those who didn't (Hollis et al., 2008).

Drawbacks:

Time-consuming and burdensome

May promote unhealthy food relationships

Overlooks nutrient quality

Often inaccurate (20-30% underestimation common)

Ignores other health factors (exercise, sleep, stress)

Rarely sustainable long-term

A 2019 review linked rigid calorie counting with increased disordered eating behaviors (Linardon & Mitchell, 2017).

Calorie Awareness: A More Flexible Approach

Calorie awareness focuses on understanding approximate energy content while honoring hunger cues and food quality.

Key strategies:

Learn typical calorie ranges of common foods

Understand portion sizes visually

Pay attention to hunger and fullness

Prioritize food quality over just numbers

Be mindful of high-calorie, low-nutrient choices

Keep simple food notes without exact counting

Research shows promise: a 2019 JAMA Internal Medicine study found simply reducing ultra-processed foods led to weight loss without explicit calorie counting (Hall et al., 2019).

Instead of meticulously tracking every calorie, consider a balanced approach of general awareness, hunger cues, and focusing on nutritious whole foods.

Conclusion:

Calories matter—they're the energy units that fuel our bodies and affect our weight. However, focusing exclusively on calorie counting often misses the more complex and individualized nature of nutrition and health.

The key takeaways from our calorie exploration include:

Calories are important, but calorie quality matters just as much as quantity

Individual caloric needs vary significantly based on age, sex, activity level, and metabolic factors

Estimating calorie needs provides a helpful starting point, but requires adjustment based on results

Being aware of calories without obsessively counting them may be a more sustainable approach for many people

For children, nutrients for growth should be prioritized over calorie restriction

Remember that nutrition science continues to evolve, and our understanding of calories and metabolism is still developing. The most effective approach is often one that's personalized to your unique body, lifestyle, and goals.

Stay tuned for my next blog post, where we'll explore how to create a sustainable calorie deficit that works with your body rather than against it, effective strategies beyond simple math, and how to combine calorie management with other lifestyle factors for optimal results. Subscribe to my page for more updates on nutritional knowledge that can transform your relationship with food and health!